Is It Fair to Compare the Fall of Rome to Now?

Scrying America's Future by Comparing Rome's Past

“Everyone, deep in their hearts, is waiting for the end of the world to come.”

-Haruki Murakami

There’s been a lot of talk about the Roman Empire lately. As a full-blown Rome nerd, I always figured this sort of thing would make me happy. After all, in addition to meme pages dedicated to Rome and Rome-based memes getting millions of views, there’s even been a TikTok trend about Rome. Many were surprised at how often others thought about Rome. I found myself dismayed and confused at how little many people thought about Rome, but that’s nothing new.

However, it does appear that more people than average are thinking about the Roman Empire largely due to the “late-stage empire vibes” many are getting. Comparing the collapse of the Roman Empire to the current gnarly state of affairs in the West, especially the United States, has become increasingly common. I imagine readers of this blog have encountered this trend in either conversations or memes like this:

It’s common — but is it accurate? It’s worth exploring, and not just for pedantic reasons that lead to a “well, actually…”. As historian Amaury de Riencourt points out (repeatedly and in great detail) in his excellent book The Coming Caesars, the parallels between Roman history and American history run deep indeed. In his model, America is to Europe as Rome was to the Greek world. Rome inherited much of Greek culture, and eventually vassalized and then conquered it out of a complicated necessity. The United States was intentionally modeled on the successful aspects of Rome, as well, and its founding values of frugality, practicality, and hard work are very similar. Looking to the Roman past is as close to a crystal ball as we’re going to get.

So, the questions I’d like to address today are the following:

Is it fair to compare the fall of the Roman Empire to now?

What parallels can be drawn between a declining Rome and the current state of Western civilization, and especially the United States?

How can modern people use this framing mechanism to understand their unique place in history?

Here is an initial conclusion: It is inappropriate to draw direct connections between the end of the Roman Empire and the current state of the United States or the West in general. Not even close. But the Roman Republic? Now that’s another story entirely.

How long did you say?

Some context, first. Rome existed as a political entity in many forms for nearly 2,000 years. To make the briefest possible summary, its political history can be divided thus:

The Roman Kingdom (753-509 BC)

The Roman Republic (509-27 BC)

The Roman Principate (Empire phase 1: 27 BC-284 AD)

The Roman Dominate (Empire phase 2: 284 AD-476 AD (this period is messy and I’m vastly oversimplifying))

The Eastern/Byzantine Roman Empire (until 1453 AD)

That’s a lot of history to draw on. So, this is why we need to get more specific when we talk about the collapse or fall of the Roman Empire. Which Rome? Which collapse? What specifically can we compare today to?

Misunderstanding Collapse

The Course of Empire: Destruction, by Thomas Cole (1836)

When people think of the fall of Rome, they often think of a painting like the one above: A disastrous short period of time in which everything went to hell in a handbasket.

But that’s not at all what happened to Roman civilization. The decline of the Western Roman Empire took centuries, beginning arguably at the end of the 2nd century AD with either the Antonine Plague or Emperor Commodus, accelerating during the Crisis of the 3rd Century, and undergoing a period of renaissance after Emperor Aurelian helped patch the empire back up in the 270’s AD. Things got nasty again in the second half of the 4th century, and didn’t really get better from there.

So, rather than collapse, decline is a far more appropriate term (which is why Gibbon used it). The decline was a long, slow, painful, and not always obvious process punctuated by moments of crisis. But that’s complicated, and internet memes aren’t, and I get that, and it’s OK. You can’t fit complex thoughts into short-form content, and overanalysis makes things unfunny. As a fun example of missing context, the popular painting above that for many summarizes the fall of Rome is part of a 5-part series of paintings depicting the life cycle of empires. I recommend checking it out.

Where’s the Fair Comparison?

Cicero addresses the Senate during the Catiline Conspiracy, by Cesare Maccari

A common mistake is to refer to the Roman Republic as the Roman Empire. They were very different times. Most of the famous Roman names your average citizen knows now — Julius Caesar, Cicero, Cato, Pompey, Crassus, Augustus, Marc Antony — come from the very end of the Roman Republic. It was a truly tumultuous time filled with some of the most famous people to have ever lived. But it was the culmination of a time of turmoil that had lasted generations already.

An excellent description of the leadup to the final act of the Roman Republic can be found in Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before the Storm, which describes the turmoil beginning around 130 BC and finishing around 80 BC with the Civil War between the forces of Sulla and Gaius Marius.

If we were to make as direct a comparison as possible between the United States and Rome, and try to put it somewhere on the Roman timeline, the closest parallel would be towards the end of the 2nd century BC when Duncan’s book begins, as it had become clear Rome was going the wrong way. A combination of widespread social problems, corruption, and external threats led to spiraling political violence that took a century to play out. It arguably began with the Tribunates of the Gracchi brothers, both of whom were murdered for attempting populist reforms that infuriated the ruling class.

Going through all the mental gymnastics to draw as many direct parallels as possible is largely a waste of time — it’s much better to look at the broader context. After all, the United States has never suffered a major invasion like that of Hannibal or the Cimbri and Teutones, and further, things happen much faster now. There’s also nukes.

But other parallels are quite apt. Two clear factions emerged fighting for dominance, representing elitist and populist classes in the optimates and populares, respectively. External conflicts gave opportunities for leaders and upper classes to gain more power. Rome became increasingly urban and sophisticated, while its backbone of freeholder farmers dwindled. Its demographics changed rapidly. It rapidly became a true military superpower. And, while voting rights consistently expanded, common people were often getting screwed. This list could be much longer, but I think that’ll do.

My take is this: The United States is at the beginning of a protracted period of conflict. How long exactly it lasts is anyone’s guess, but internal political violence is still minimal compared to Sulla’s Proscriptions, for example. And we sure as hell haven’t reached our stage of Caesarism yet, in which remarkable individual leaders gain more and more power. Our current leaders are remarkably unremarkable and it’s almost certain no one will be talking about them 2,000 years from now. So what can we expect? Both internal and external conflict, difficult times for average people, and the rise of both demagogues and virtuous leaders.

Periods of conflict produce powerful leaders by necessity. More conflict means more chances for leaders to emerge and ride waves of turmoil to power. Conflict makes for interesting times — which are bad for ordinary people, but great for history books.

Of course, there are plenty of potential disagreements with the trend I propose, like models that attempt to identify patterns in history. Strauss-Howe generational theory puts us squarely in the middle of a period of crisis. Peter Turchin has his own take on historical trends with Structural-Demographic Theory. Sir John Glubb argued that the average lifespan of empires was around 10 generations, or ~250 years. That’s just a few examples. For now, I’ll stick with my take.

The Caesarism Conundrum

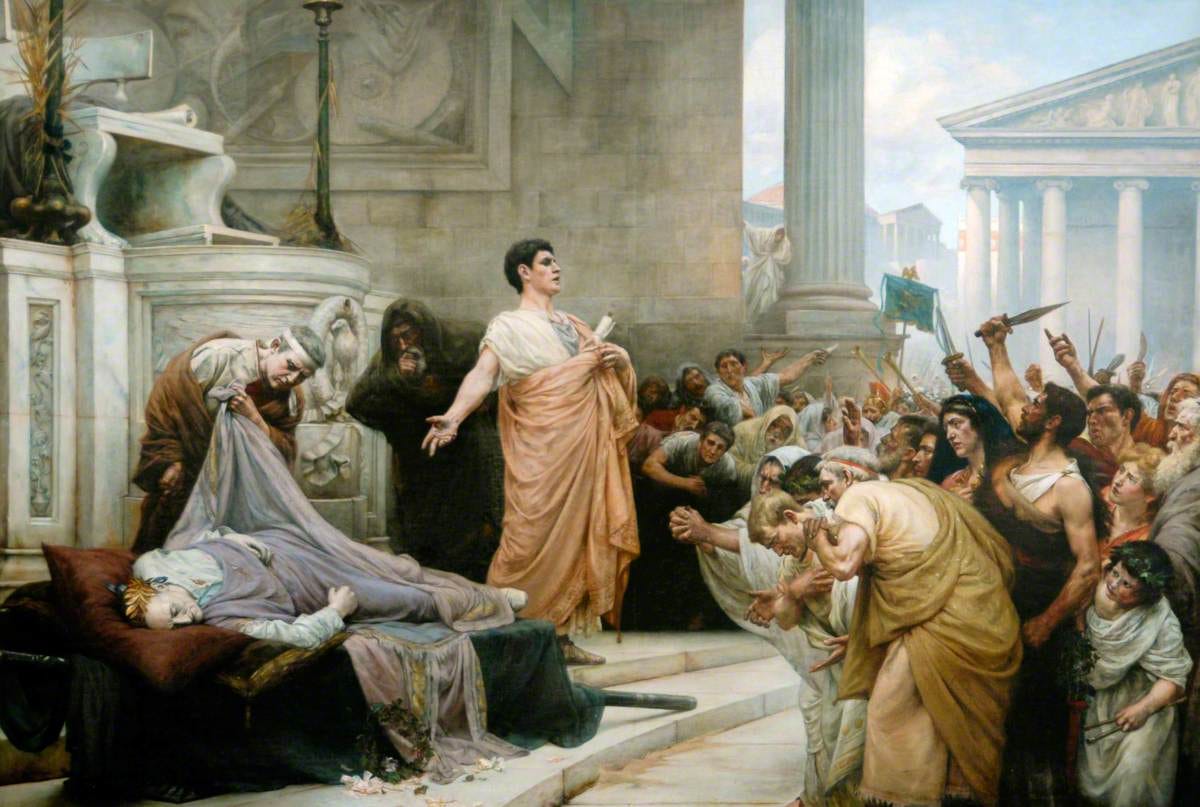

Marc Antony’s Oration at Julius Caesar’s Funeral, by George Edward Robinson

Should the world slide into conflict — as it certainly appears to be — at the same time that political violence becomes an entrenched trend in America, we can expect a period of Caesarism that de Riencourt proposes in his book.

But as I’ve written before, the constant struggle between centralized power and entropy could easily go entropy’s way. Despite its immense power, the United States is more fragile than Rome ever was. Rome didn’t have a power grid that could be knocked out, or hackers who could take down infrastructure, or a communication network that relied on complicated electronics and satellites. Its enemies didn’t have nuclear weapons and hypersonic missiles. Although its economy was complex, it was orders of magnitude less complex than the one we have now. And it didn’t ever experience a population boom that saw the world population jump by a factor of 8 in two centuries.

So, should a collapse happen today, it would be significantly swifter and far more brutal than any that happened in Rome. The power grid going down for a month would be all she wrote, and that’s just one scenario. The point here isn’t to frighten anyone — it’s to indicate we’re at a real turning point and live in a unique time in history, unless you’re a fan of antediluvian civilization theories.

On that note, hey, here’s a suggestion: Maybe we should stop willing a collapse into existence? It doesn’t have to go this way at all. Most people in the world want peace, same as it ever was. Governments only have the power their citizens collectively allow them to have. I’ll have to save my diatribe on decentralization for another post, but suffice it to say I think that’s the best way to prevent catastrophe.

Finally, to end on another, more positive note, here’s the long run: Should we get through this seemingly inevitable upcoming period of turmoil, there’s a golden age waiting on the other side of it. Who will be the Caesar Augustus who brings peace? Who will be our equivalent of the Five Good Emperors in the 23rd century? I’d love to find out.

I know the term is overused, and one of the reasons perhaps you’ve avoided it here, but we are manifesting collapse, in my opinion, rather than willing it.

We are consumed by the doom cycle, on average, and unable to take the time and introspection as a whole to see the light at the end of the tunnel quite yet. It just quite obviously appears things are done, if that’s all you hear, and happen to be a naive and/or not particularly curious person.

The only way that our situation would truly resemble Rome is if NHI are interested in resource control and capable of invasion, and that certainty remains to be determined. And I’m really not joking, nor holding my breath.

The US still has an awful lot of potential to mature, and it is still so, so experimental in the arc of history. Sometimes it really hits me, living in a largely ethnically homogeneous country, how incredible a thing is being attempted, and how utterly uncontrollable it ultimately is.

Thanks for the article, it was great.

The common conception of the hall Rome is mostly about the collapse of the Western Empire in the 5th century, but the Eastern Empire .. the Byzantine Empire .. motored on for another 1000 years until the rise of the Ottoman Empire. If there are parallels from a collapse perspective do they relate just to the Western Empire? (rhetorical question) If so, it could be a looming event, but if it relates to the end of the Byzantine Empire as well, there maybe some juice left to squeeze out if this orange.