The Hobbesian Dilemma: Centralized Power and Entropy

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

-W.B. Yeats, The Second ComingOk, full disclosure — I know opening with a quote is often overdone. But if there’s any appropriate time for that particular poem to be cited, it’s now and in this article. Besides, there’s nothing quite like a dramatic entrance, and the sense of foreboding is spot on.

After all, you may have felt it — a looming unease, or that things are not right, or a general feeling of danger. To say that the last few years have been anxiety-inducing is an understatement, but the full cause of that anxiety may be mysterious.

Well, let’s dispel that mystery. The truth is simple: We’re at one of the great turning points in history. People may not know it directly, but they feel it in their bones. It’s like genetic memory tells us when these things happen.

That’s because there have been many times of great change, and so far our species has successfully navigated all of them. We’re still here, after all — so that’s reassuring. You are the descendant of the smartest and luckiest people to have ever lived, and your existence is evidence of their triumph. Before we get too deep in the weeds, let’s take a moment and remember that.

So, here’s where we are: We’re at the tail end of the largest growth in population and wealth in human history. Our countries are the most powerful to have ever existed, and our technology would be magic to previous generations. But our limitations are visible on the horizon, and the trend towards infinite growth is slowing — and in many ways reversing.

It’s hard to digest the big picture all at once, so we’ve got to cut it into bite-sized pieces. A large part of this turning point is due to what I call the Hobbesian Dilemma, named after the 17th-century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes. It goes like this:

Governments must grow and centralize increasing amounts of power to counter both internal and external threats

Governments then grow too large to be efficient and eventually collapse under their own weight after mismanaging threat responses

This trend is one of the dominant cycles of history, and we’re seeing it play out in real time. Like militaries, governments are built to handle the last crisis — not new ones. For example, the biggest threat to countries in the 20th century was other countries, so centralized governments became enormous. But the ever-increasing cost of maintaining those states combined with the growing power of non-state actors means massive, centralized governments no longer work.

Think of our current states like heavyweight boxers. A heavyweight boxer is an expert at fighting other heavyweight boxers — but is useless against a beehive or a bacterial infection.

The beehives and bacterial infections we currently face are many, but the two I’d like to focus on for now are fiscal mismanagement and the growing power of non-state actors. As non-state actors gain influence worldwide, states have to expend increasing amounts of blood and treasure to maintain their own dominance. They’re doing so poorly, and we’re currently witnessing the consequences. For now, I’m referring to non-state actors specifically as non-state aligned combatants — since delving into the influences of business, religion and more is too big a can of worms to gulp in one go.

So, where are we headed, you ask? Weakened centralized states everywhere. A trend towards decentralization and deglobalization. Increased autonomy for regional powers and lessened international trade. In short, the center cannot hold.

I owe you an explanation for these assertions, so let’s start with a good ol’ bit of background, starting with the widely influential writings of Thomas Hobbes.

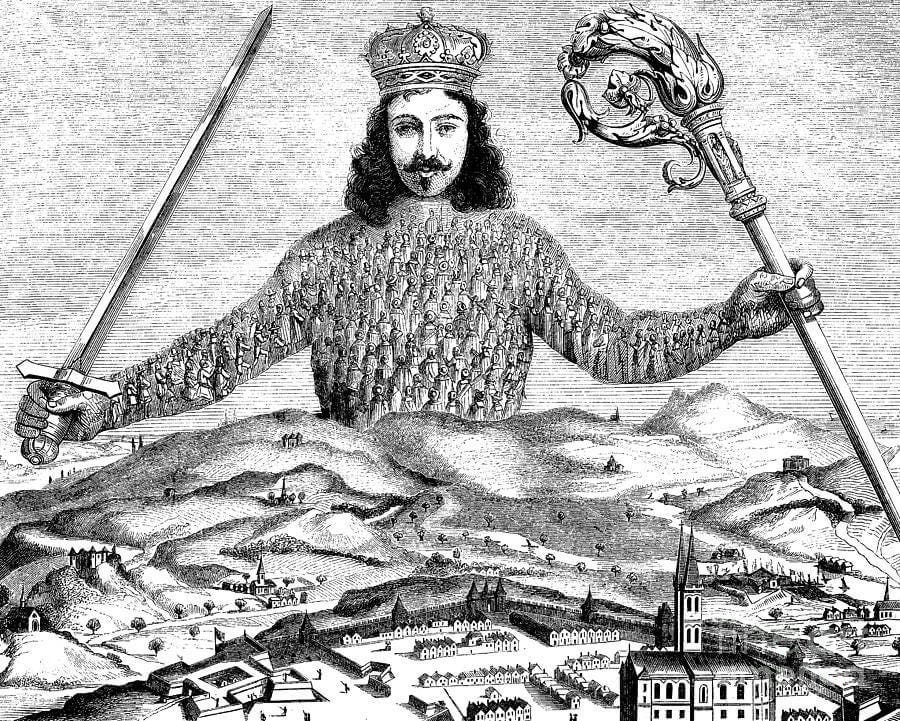

The Viable Leviathan

By far the most important takeaway from any of Thomas Hobbes’ writings, chief among them The Leviathan, is this: Power, or the monopoly on violence, must be centralized in order to prevent chaos. As Hobbes put it, the Natural State is that of the war of all versus all.

So, why did Hobbes believe what he did? Consider the times he lived in. The Leviathan was published in 1651 in England, which had just witnessed a bloody civil war. Meanwhile, the continent of Europe had been ravaged by the religiously-driven Thirty Years’ War of 1618-1648, which had claimed the lives of nearly ⅓ of the citizens of modern-day Germany among countless others. Its combatants included France, the Habsburg empire, countless German principalities and small states, Sweden and more. That’s almost all of Europe at war for two generations.

So, when Hobbes wrote The Leviathan — which he wrote during the English Civil War — he was witnessing a world in total conflict. It was indeed a war of all against all. The logical conclusion was for a single entity (read: the State) to maintain a monopoly on violence so complete that no one could challenge its rule.

This absolute monopoly on violence was meant to solve two problems. First, it would prevent the banditry and lawlessness that become common in war-torn regions. Second, it would prevent any rival claimants to power from stepping out of line—since, y’know, civil wars are a bit disruptive to economic and social stability.

Hobbes’ ideas don’t seem very radical to us now, but they were quite heterodox at the time. Recall that England had had checks on the power of its monarchy for 400 years, while Europe in general was still a feudal society that balanced centralized royal power with that of local nobility. Arrogating supreme power to one person may have seemed extreme, but to Hobbes it was a necessary move.

Now, claiming that absolute centralized power has its foundations purely in Hobbesian thought is shortsighted and untrue. This idea was far from new, though its purpose was arguably best summed up by Hobbes. Centralized power dating back to the empires and God-kings of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China followed such models. The more organized and well-funded the centralized state was, the more secure the empire and the lives of the people within it were.

The idea remains today: Centralizing violent power into a single entity is common practice. Think about it: Who holds the monopoly on violence where you are? Is it the police? If so, congratulations — that’s the State. If not, depending where you live, you may indeed prefer it were the State.

Diminishing Returns

The problem with strongly centralized regimes is they rely on ever-increasing levels of energy input in terms of manpower and money, i.e. blood and treasure, to maintain their gravitational pull. As centralized power grows, so does its inefficiency, since increasingly complex structures require increasing governance — with no accompanying guarantee of increasingly competent administrators.

Eventually, there comes a tipping point at which an empire can no longer sustain its military and civil expenses. This may come from internal disruptions, like plague, civil strife, or corruption, or it may come from an external disruption like war. Historically, when an empire chooses to debase its currency to continue funding its military or social programs, the tipping point appears — and in most cases, it denotes the high water mark of that empire. That’s when the entropy kicks in, and the loss of centralized power is inevitable.

It works much the same as a star: The largest stars burn themselves out fast and collapse under their immense weight. Small stars, for comparison, can last a very long time.

Fast Forward to Today

If you’re wondering why I’m writing about 17th century philosophers and wars, stay with me here. There are lots of connections to make.

First, in recent decades the United States has maintained a level of dominance over the world (and Europe) that hasn’t been seen since the height of the Spanish empire, the Louis XIV era of France, or the Victorian era of Great Britain. The United States is the modern Leviathan. But it’s clear that American dominance is waning, and for the same reasons.

Spain squandered its enormous New World fortunes on a number of wars, most notably the disastrous 80 Years’ War. This conflict was funded by massive silver imports that eventually diluted the value of the metal, and thus inflated away Spain’s currency. Think the US’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were long? Imagine four generations of that. The country has never fully recovered: Since its peak, Spain has defaulted on its external debt thirteen times.

Similarly, after Louis XIV declared “Après moi, le deluge,” France’s series of lost wars in the 18th century, including the Seven Years’ War, cost the state its budget many times over — and it defaulted four times in that 18th century alone. We’ll get to the UK a bit later.

Clearly, maintaining a superpower is extraordinarily expensive. The law of diminishing returns means investments become untenable. Superpowers can’t be static since they require ever-increasing input in order to continue growing. This is where the conundrum of empire comes into play, which is worth some explaining in itself.

The Cost of Empire

Whereas nations and city-states can exist in perpetuity based on the labor and production of their populace, empires require expansion in order to fuel their economic furnaces. As soon as an empire stops expanding it is doomed.

This is exemplified by Rome, which had a grace period of roughly 100 years between its imperial peak (117 AD under Trajan, peace be upon him) and the Crisis of the Third Century. France had a grace period of just a few decades between its Monarchist peak under Louis XIV and the Revolution, in which the Monarchist state was destroyed and replaced. China has experienced a constant flux of centralization and decentralization for around four thousand years. There are myriad such examples throughout history, which I could happily go on about, but won’t for the sake of your attention span.

The point is this: Countless empires have collapsed because of mismanaged treasuries, especially in the form of military and social program spending. Managing spending becomes increasingly costly commensurate with expanding state power. Let’s look at examples of military spending for now, and perhaps later I’ll do another post on social programs.

Extravagant military spending: A feature of late empires

Consider the staggering costs of advanced military power, which continually escalate. The most expensive American program of the Second World War wasn’t the Manhattan Project — it was the development of the B-29 bomber, which cost $3 billion in contemporaneous dollars, roughly $45 billion today. At the time, such a cost was scandalous — even during the largest conflict the world had ever seen.

By comparison, the more recent development of the F-35 fighter ups the ante by more than an order of magnitude, with a total cost of somewhere around $1 trillion, with around $400 billion just in development. And we’ve not even used it in combat…yet.

If you’re asking yourself, “How the hell can anyone afford that?” then you’re not alone. But these are the costs of maintaining military dominance, and this is not a new story. After all, maintaining military dominance is not optional for a superpower, since superpowers beget rivals by their very existence.

Another example: One of the (many) proximate causes for the First World War was the naval arms race between Britain and Germany in the years prior to 1914. Creating and maintaining a modern fleet whose ships became obsolete as soon as they hit the water threatened to bankrupt both countries. Britain was not content to cede naval superiority to any country, and so dramatically increased its spending to outpace Germany’s.

The result? Millions died, four empires collapsed (the German, Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian), and two more were mortally wounded (the British and French). By 1919, the world’s financial center had moved from London to New York City. By 1949, the British Empire had ceased to be. The UK only finally paid back its WW1 debt to the US in 2015, and its WWII debt in 2006. Seismic geopolitical shifts, it seems, happen quickly — but their consequences are long-lasting.

Certainly, using military spending to bankrupt a competitor can be an effective tactic, as the US victory in the Cold War demonstrated. But for the last two decades, the US has simply been bankrupting itself. Countries can and do bankrupt themselves in their quest for power and dominance — or even perceived self-defense.

Conquering the World in Self Defense

It’s often been argued that Rome conquered the world in self defense. The current military-security apparatus in the United States serves essentially the same effect: In order to prevent trouble at home, we must bring trouble abroad first.

This was the argument behind both World Wars, the Vietnam War, the first Iraq war, Afghanistan, and the second Iraq War. Oh, and the Cold War — one of the most expensive ventures ever embarked upon.

It's impossible to calculate the true downstream costs of war or maintaining an empire. But we all know it and see it, which is why it’s mind-boggling or simply incomprehensible for the average U.S. citizen to see the annual military budget — especially considering recent failures. You may have a great sword, but it doesn’t matter if you’re no good at swinging it.

Consequently, when the US military gets defeated by Vietnamese rice farmers or Afghan mountain dwellers, or fails to maintain power in the comparatively miniscule nation of Iraq, the power of non-state actors and the frailty of centralized power comes into plain view — and the true cost of conflict is laid bare. Winning those conflicts would have required adopting monstrous tactics civilized sensibilities could not endure. In such a way, civilization is often its own undoing. And so, now, modern non-state actors have more disruptive power than ever before — now that they’ve sensed our weakness.

The Increasing Power of Non-State Actors

In May of 2021, the hack of the Colonial pipeline in the eastern US brought the region to a standstill. To this day, there is not much public information about the organization responsible — except that their name is DarkSide and they’re “probably” from Eastern Europe or Russia. Colonial Pipeline paid the (relatively small) ransom of around $4 million dollars to undo the damage, and life went back to normal.

But for anyone paying close attention, the disruption underscored the extraordinary vulnerability of infrastructure — as well as the bewildering power a handful of geeks with keyboards can have.

No F-35 could solve the problem. Nuclear weapons were no deterrent. The message is there: Conventional warfare is nearly obsolete. Why go to war with a country if you can cripple their infrastructure with a few keystrokes? And, more tellingly: Why have expensive centralized power if it cannot defend that critical infrastructure? Given its success, it’s clear that this attack was merely a prelude to far more destructive ones in the future.

And that’s just one example of non-state power trumping state power and making it look silly. I pulled that particular example out of a hat. But state power simply is not built to fight the asymmetric style of warfare common from non-state actors. Consider:

The ever-increasing strength and wealth of narco-traffickers in many parts of the world

The shockingly low cost of a Bayraktar drone ($5 million)

3D-printed guns and even bazookas

The incredible persuasive power amassed by and in social media

The vulnerability of communications networks and electric grids

The disruptive power one deranged lunatic with a gun can have

I could go on, but I think you see my point. The US recently lost its longest-ever war against a handful of mountain dwellers armed with antiquated equipment. It fled in ignominity, leaving behind an enormous stockpile of high-tech weapons. As an American, I was ashamed — but not surprised. That’s the way things are going, and our military was the wrong tool for the job.

We haven’t even yet touched on the power of corporations, banks, or religions, but those topics deserve their own posts. We’re currently in a moral and religious vacuum where religions have fallen by the wayside in much of the developed world — especially China. Expect that to change, with unpredictable effects. For reference, the last time China had a major religious uprising, it was called the Taiping Rebellion, led by the alleged younger brother of Jesus Christ, and resulted in some 30 million deaths. Never underestimate the power of people propelled by religious belief, or the number of Chinese that can die in a catastrophe.

And banks, well…they’re exactly what thumbscrews were invented for.

I’ll wrap this up here. Centralized power is long past its tipping point. Resources are no longer adequate to maintain the power structures that have led us until now. Non-state actors are more powerful than ever. And shit is about to get weird.