The Declaration of Independence and the Gordian Knot

Is It Yet Time for a Gordian Knot Solution?

This article was originally slated to be released on the 4th of July to coincide with United States Independence Day…but something happened. At first, I wanted this to be a piece simply re-examining the Declaration of Independence and drawing parallels between 1776 and now, as well as between the grievances listed on the Declaration and those we now may enumerate.

But I got stuck on the phrase “dissolve the political bands” and it brought me somewhere else. And like with a Rottweiler with a bone, I just couldn’t let it go.

After all, drawing connections between seemingly disparate historical events is one of my favorite hobbies — especially when there’s a good deal of modern relevance to be found in doing so. As the title suggests, the two events I’d like to examine today will be the legend of Alexander the Great and the Gordian knot and the creation and signing of the United States’ Declaration of Independence.

Both events represent lateral thinking, bravery, boldness, and creativity. Both were part of dramatic upheavals that forever changed the landscape of history. Both reveal powerful insights into human nature at its finest. And both provide lessons we can draw from today in many different ways.

Independence Day is a yearly reminder that revolution can be possible, honorable, and necessary. In the past, it was simpler and happier day. But celebrations of successful revolution hit differently when your government is clearly corrupt — an assertion I’ll make without feeling the need to elaborate here. For me, this year, Independence Day led to a good deal of soul searching. This bit of writing is the result.

So, the key question I’d like to address in this piece is this: Is it yet time for a Gordian Knot solution to the political ills that plague the Western world, and more specifically the United States?

There are many among us who want change, and significant change at that. We are far from alone historically: Revolutions and wars, both successful and not, litter the pages of history. But are we ready for such change?

On the Same Parchment

Before we get into analysis mode, let’s make sure we’re all on the same…well, parchment. While the Declaration of Independence is widely recognized as one of the most important documents in the history of politics or political philosophy, I doubt many people, American or otherwise, could accurately recall it fully. So, I recommend taking the mere ten minutes or so required to read the document. Having it open as a reference will be valuable from here.

Second, while we have far less exact records of the legend of the Gordian Knot, the important points are fairly well-established. The Gordian Knot was a legendary knot associated with royalty in Phrygia, in what’s now Turkey but at the time belonged to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. As the legend goes, it was impossibly difficult to untie in an almost magical way, and whoever would find a way to untie it would become the ruler of all Asia (as Anatolia was known then, though the idea was a bit nebulous). In 333 BC, at the very beginning of Alexander’s invasion of Persia, Alexander was challenged to untie the Knot. He famously solved the knot and thus fulfilled the prophecy, later going on to conquer the entire Persian empire and become emperor himself.

How exactly he solved the knot is up to some debate, but the most common interpretation is that he dramatically severed it with a single sword stroke. Other sources argue that he untied the linchpin that kept it tied to its oxcart, but the exact method doesn’t matter. Rather than assiduously untying the knot, a simple, swift maneuver that others simply hadn’t considered was the key to solving the impossibly complex problem.

Strokes of Sword and Pen

And here is where the comparison between the two events first becomes evident. As noted in the Declaration’s opening line,

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Specifically, the portion that describes “dissolving the political bands which have connected them to each other” stands out. The connection between government and governed is often impossibly complex, as was the Gordian Knot. The Declaration resembled Alexander’s slashing of the Knot by seeking to undo it entirely, though one might wonder if Jefferson would later have wished he had used a verb like “severed” rather than “dissolved” to describe undoing those political bands. Those bands were quite strong.

The similarities of the two events are striking. The trials of both Alexander and the Continental Congress had just begun with each event. Alexander would wage war for the next ten years until his death, while the signatories of the Declaration found themselves engaged in a war that would rage over the next five years and claim the lives and fortunes of many.

Alexander and his allies found themselves fighting the most powerful empire of the time; the Continental Congress did as well. Both were outnumbered, out-funded, and not taken seriously at first by their Imperial enemies. Victory was far from guaranteed. Yet both succeeded beyond their wildest dreams, and left an indelible mark on history we still feel today.

The similarities don’t end there, though. Raised as a prince and educated by none other than Aristotle, Alexander was exceptionally well-heeled and educated. The Signatories of the Declaration of Independence, while not royalty, could comfortably be described as aristocracy, with extensive educations, businesses, and properties. Regardless, all were regarded with some degree of derision by their Imperial foes as rubes.

Furthermore, despite the roughly two thousand years that separate the two events, the concept of “sacred honor” would have rung true among both groups.

Is It Time Yet?

So, back to the initial question: Is it yet time for a Gordian Knot solution and to sever the political bands that connect governed and government?

I would suggest that it is not yet time. This is for three specific reasons, which I will examine in greater detail:

We are not yet prepared

Poorly-led revolutions have a history of going horribly wrong, and we currently have poor leadership

Reform can and must be pursued to salvage what’s salvageable

To be clear, I’d like to present a brief list of broad assertions that readers are free to disagree with should they see fit:

Many Western Governments are inadequate and failing in their responsibilities to their citizens

The consent and will of the governed, in many cases, has been ignored by said Governments

If we do not act now to rein in Government power, we will find ourselves and our progeny mired in inescapable Tyranny

So, we’re at a point where we must change our relationship with our governments, and thus our governments themselves, but we are not ready for a full-on revolution yet. Allow me to explain with examples. I will largely be focusing on the United States, as the de facto leader of the Western world at the moment, and where dramatic change would have the most impact. Feel free to extrapolate ideas to your specific locale.

We Aren’t Yet Prepared

Let’s consider our two examples from the introduction. Alexander the Great received command of what was the most effective armed force in the world at the time, though not the largest. That army was created painstakingly over decades by his father, forged through training and discipline, and created in part as a result of Philip’s own captivity: His observation of the Theban military gave him inspiration for his famous Sarissa-bearing infantry and high-quality cavalry, the latter of which Greeks were not known for. Philip’s hiring of Aristotle to tutor his son indicates how highly he prized education and intellect.

In short: Had there been no Philip II, there would have been no Alexander. Had there been no Aristotle, there would have been no Alexander. Alexander’s conquest and triumph was the product of generations of genius.

And now consider the context in which the American Revolution took place. The American Colonies of the late 1700’s were filled with hardy, independent-minded, hard-working and often well-educated people. Many men had served in militias in frontier skirmishes or had fought in the Seven Years’ War (known in the US as the French and Indian War). The educated classes were part of a rich philosophical movement that produced great works we still read. It’s no accident Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776, the same year as the Declaration was written.

Again, the men who would lead the American Revolution were the product of generations of talent and of their own specific time. Decades of hard work, education, and attempted reform were the fertile soil from which revolution sprang. We’ll come back to “attempted reform” later.

I’d posit that the crisis the United States is undergoing has just begun, and one could extrapolate that crisis more broadly to the Western world in general. This crisis of fiscal mismanagement, blundering foreign policy, corruption of government officials, intrusion of government into private life, poorly-managed migration, and much more isn’t going away anytime soon. To imagine problems disappear without significant effort is magical thinking.

But generations of easy living have created people ill-prepared to force positive change upon society. If we have just now entered hard times, those hard times have not yet created strong men. Should that maxim hold true, we will not have the moral and intestinal fortitude necessary to create a viable, lasting, and wholesome revolution for some years to come.

Caveat: The hard times coming may not leave us ample time to create a new generation of strong people. With fiscal and debt crises looming, war on the horizon, and demographic calamities already underway, those who have hitherto enjoyed comfortable lives may find themselves required to step up to meet challenges.

Poorly-led Revolutions Go Badly

Americans consistently and rightly look to their Founding Fathers for guidance. That generation was unique in history and provided much-needed leadership for the Revolution they shepherded.

But we currently live in an age where distrust of institutions and official leadership is at an all-time high (American stats). There are very few leaders willing to stand up to the corruption and mismanagement that clearly plagues our national government(s). Those who claim to do so quickly become mired in that very same corruption. Indeed, the condition seems to be contagious.

In sum, the leadership we have is wholly inadequate to our needs. By “leader” here, I don’t simply mean “politician.” I mean, “Someone whose opinions and actions you respect, and to whom you would be willing to grant power.” A new generation of leaders will have to be created after succeeding in difficult conditions and proving their merit. Good leaders are a feature of the human species and arise spontaneously, but are not guaranteed.

They’re entirely necessary for successful change, however. Revolts without solid leadership generally go very poorly. For every successful peasant rebellion, there are hundreds of failed ones. In recent years, the Occupy movement was perhaps the most classic case of what a leaderless attempt at revolt looks like. It correctly diagnosed its enemy and the problem facing the nation in the form of capital institutions co-opting government and society, but had no plan to dismantle or replace it.

Thus, the body politic may be rife with malignant tumors, and laymen may observe and diagnose it. However, as with cancer in real patients, a specialist is still required to successfully treat and remove the cancer without killing the patient. In this case, that would be the leaders necessary.

In short, any successful revolution must have both leaders and the public driving it, like the two wheels of a cart. But leaders of revolutions can be wolves in sheep’s clothing, leading societies into far worse situations than they had previously experienced.

The most commonly co-opted type of movement is a populist movement, which are susceptible to strong, fanatical leaders. Populist revolutions that ended up being led or co-opted by vicious ideologues have been numerous, and recent examples include:

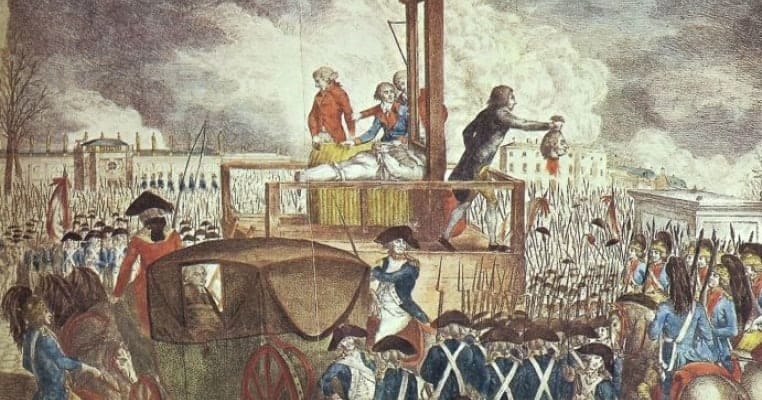

The French Revolution

The Russian Revolution

The Chinese Civil War/Communist Revolution

The Khmer Rouge Revolution

This is far from an exhaustive list, and going into details on each can and does fill numerous books. In each case, however, bloodshed and violence overwhelmed the original populist intent of the revolution due to malign leadership. Thus, I would caution anyone in favor of any attempt at revolution to very, very carefully vet their leaders. And I’d also caution that many of those pushing revolt in the US are not your friends and do not care one whit about the well-being of its population.

Reform Is Still Possible, Or at Least Must Be Tried

The Declaration notes that it is the Right of the people to “alter or abolish” the government that is failing it. Alteration is far preferable to abolition, since the latter would get ugly.

Consider previous attempts at alteration. For the Continental Congress, revolution was far from the first stop. Rather, as subjects of the British Crown, they had attempted countless legal methods to resolve their disputes with their government. Consider the Stamp Act of 1765, which rightly encountered much ire in the Colonies. Its repeal the year after its enactment was the result of significant pushback, including protests in the streets and hanging of officials in effigy.

That a decade took place between the Stamp Act and the Declaration shows how glacially things can move until they finally snap. It also demonstrates the power of organized resistance against government overreach.

Clearly, the attempts to peacefully resolve disputes failed and led to the Declaration. But the attempts were necessary to provide a moral framework within which real change could happen. Crucially, attempting to legally produce change provided legitimacy to the grievances enumerated in the Declaration.

Within the Declaration, after the 27 charges levied against King George III’s government, readers can find a crucial and often-overlooked line that provides valuable context. Simply, it reads:

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

In other words, they could say, “Look — we told you about these problems and you didn’t do anything about it. We tried to be reasonable, but that failed, so now we have to escalate.” There are methods stronger than voting but far from violence that must be explored.

Let’s snap back to now. Are there any good examples of positive changes within legal channels to amend government abuse?

The Missouri v. Biden case, which restricts a number of Federal agents from contacting social media companies to censor free speech, is one such example of a way forward. The case will likely end up at the Supreme Court and may yet prove one of the most landmark decisions in the country’s recent history.

Is this case enough to turn abuse of the Constitution around? Far from it. But it provides at the very least a template to curb government overreach by relying on a judicial system that is not yet wholly corrupt. It’s a necessary step and a morale boost that demonstrates there is still hope to save the system from itself.

If you’re looking to push for reform, remember: He who would move mountains must begin with small stones. A good start is constructing a list of grievances with one’s government, like that found in the Declaration. Then, consider if those grievances can be reformed through legal channels like lawsuits or if they’re simply irredeemable aspects of the regime.

This act is not some frivolous list-making for the sake of making lists. First, the Declaration itself recommends it in the preamble. Second, it helps you or whatever group you associate with decide just what trespasses from the government are most egregious and most important to you. If there is significant overlap between your list and that of another individual or group, you have just found common cause — and thus your movement may strengthen. You will quickly find out who your opponents are as well. This is different than protesting on a single politicized issue, as a holistic overview of trespasses gives a more comprehensive idea of the big picture.

Beware Both Haste and Sloth

Depending what corners of the internet you peruse, you may have seen something like the above. But rushing headlong and unprepared into a conflict is foolish. So is allowing abuse without action. Rational and measured action is the best way to effect change without losing control of one’s movement towards more radical actors.

We are made of different stuff than our forefathers, and the context in which we live is markedly different. The time is not now to attempt to topple a government without any plan as to what comes next. That does not mean change is not necessary — indeed, change is very necessary. But our societies are far more fragile than we’d like to believe, and disruptions could lead to far more chaos than anyone bargained for.

Further, those who push revolution may not have your best intentions in mind. The best way to prevent a revolution is to have a stable society. Consider that attacks on the very foundations of society, such as family structure, religion, and national identity may indeed be on purpose to usher in a revolution that can be co-opted.

Note that I have not enumerated my particular grievances with my government here, nor have I suggested a solution. This is for two reasons. First, for now, I’d not like to color readers’ imaginations with my opinions. Second, I’d like to keep some powder dry for an upcoming article to explore those ideas.

If you’d like some homework, enumerate what grievances you find the most compelling. You don’t need a list of a full 27 like in the Declaration, but maybe start with ten. I’d be curious to hear what readers have to say. That can be a springboard to figuring out what can be done about those problems — ideally, peacefully.

Any revolution that seeks to remove an oligarchy while trying to replace it with something smaking of democracy would end up in bloodshed. The American "revolution" was the action of an emerging oligarchy against the perceived actions of a tyrant. But one thing they didn't want was democracy:

On the morning of May 29, 1787, in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, Edmund Randolph, governor of Virginia, opened the meeting that would become known as the Constitutional Convention by identifying the underlying cause of various problems that the delegates of thirteen states had assembled to solve. “Our chief danger,” Randolph declared, “arises from the democratic parts of our constitutions.” None of the separate states’ constitutions, he said, had established “sufficient checks against the democracy.”

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/democracy/our-chief-danger

The Gander should look into Aristotle's description of political systems: oligarchy, tyranny, democracy and his analysis into those, as well as the two Davids' "The Dawn of Everything" to have a sense of the potentiality existent....

“Look — we told you about these problems and you didn’t do anything about it. We tried to be reasonable, but that failed, so now we have to escalate.” Sounds like what Putin said to the US/NATO.

To me the problem is dealing with the sociopathic personalities who populate leadership positions - whether corporate or political. Like a narcissist one cannot reason with them - they don’t do positive-sum games - only zero-sum and they never seem to have enough.

Sorry to sound so pessimistic in the face of your hopeful writing that a peaceful way out from the increasing oppression can be found - I can’t help but think that the horse had already bolted and the new unofficial power structure is implanted. It’s been decades in the making.

My concern is that the US (and NATO) is going to implode under its debt burden and chaos will ensue (chaos is already here in the cities). That void will be filled by an opportunist - and in my reading opportunists are seldom forces for the common good.

The US has been through similar times a century ago and put in place laws and organisations to prevent recurrence - these laws have been rescinded under successive presidencies (thanks to lobbying which should be banned), Citizens United should be repealed, and NATO (whose sole purpose was to defend against the USSR) should have been dissolved when the USSR fell.