Russian Expansion and the 21st Century Great Game

The roots of the war in Ukraine are far more complex than many understand. Ukraine is a pawn in a centuries-long Great Power chess match.

So, there’s a terrible war going on in Ukraine. What was intended to be a quick operation from Russia has stalled and turned into a grinding war of attrition. You know that. You may have also heard that the roots of this war go back to 2014 in the Maidan Revolution, in which the pro-Russian government of Ukraine was overthrown — with the backing of the United States — and replaced with a pro-Western government.

Many also argue that the annexation of Crimea or even the poorly drawn borders in the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 are the proximate causes of this war. Certainly, they play a role.

But those arguments are short-sighted and miss the big picture. In reality, the war is a culmination of centuries of Great Power policy clashing in an unfortunate Ukraine. This fight was written in the stars long ago, pursued by powerful yet obscure individuals, and is the love child of fools. And it’s the most dangerous situation we’ve ever been in.

So, let’s get specific. There are three trends converging in Ukraine:

A return to form for Russia in pursuing their traditional policy objectives of securing their borders and ensuring access to warm-water ports

A continuation of a centuries-long policy, led by the UK and now the US, of containing Russian expansion, in all of Russia’s forms (Imperial, Soviet, and current)

An alarming rise in bloodlust and aggressive actions and rhetoric that’s making the situation rapidly escalate, which now threatens to engulf the whole world

I want to be clear: I want peace. War is a contagious cancer that spreads fastest in times of uncertainty and instability. So, consider that none of what I write here is an apology for Russian actions in Ukraine, nor is it intended to bolster Western (largely NATO) aims. That the opportunity for peace was dashed by a Boris Johnson visit to Ukraine in April indicates that NATO is interested in pursuing this war rather than seeking peace. And there’s much more to strengthen that point, which we’ll get to later.

Anyone with a heart and a love for humanity should want this fight to stop before it gets out of hand. We’re one misstep away from full-blown nuclear war, which is why you’re seeing PSA videos for nuclear preparation in New York. Nobody wins that fight. A negotiated peace is the only way forward. But for that to happen, we have to remove the ideologues running American foreign policy, since they’re the ones really driving the NATO bus. It’s an uphill fight against the pro-war propaganda, but it’s one we have to take on — because this bus is headed straight off a cliff, and no one is even trying to swerve.

Those that suffer the most in a war are always the people on the ground. I don’t want to see another soldier or civilian die in this war. I don’t want to see Europeans suffer a cold winter due to energy shortages. But it’s not looking like the war is going to stop. If we want it to stop, we have to understand the reasons behind it — which are far deeper than many understand.

So, let’s look at how we got here — because it’s really a hell of a story.

Russian Expansion: Do or Die

There’s a beautiful cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia, called the Kazansky Cathedral. That’s it above. Built in the early 19th century, it was named in honor of the Orthodox saint Our Lady of Kazan, the patron saint of that city.

The cathedral was built as a commemoration of one of Russia’s earliest triumphs — that of the bloody conquest of Kazan, one of Moscow’s eastern neighbors and rivals, after a war that lasted quite some time. By “quite some time,” I mean more than a century. The Russian conquest of Kazan officially began in 1438 AD, and finally ended in 1552. Yes, things used to move much slower than they do now.

While the name of the Kazansky Cathedral is a dead giveaway as to its heritage, another building — one far more famous — was constructed to celebrate the victory, and much earlier. That’d be St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. Yes, that’s the one in Red Square with the iconic onion-shaped domes built by Ivan the Terrible. That such an iconic building has its roots in a military victory over a neighboring rival should give you an indication of just how important this conquest was to modern Russia and its identity.

For reference, Kazan was a remnant state of the once-great Golden Horde — itself a remnant of the once-great Mongol Empire. What’s now Russia had suffered far worse than any other European state in the Mongol invasions and further under their domination. They’ve never forgotten it, and it’s become part of their national identity.

That Russia’s identity is forged around both being invaded and conquering its neighbors is no accident. When you’ve been invaded by the Mongols, Napoleon, and Hitler — among countless others — border security becomes priority number one. The entire area that’s now the Russian heartland — the area centered around Moscow — is indefensible flatland that requires pure brute force to maintain sovereignty. There was no other option in the past: either conquer or be conquered.

That maxim combined with a need for sea access has defined Russian foreign policy for centuries, as it’s desperately sought to expand to find natural, defensible, and economically viable borders. That practice continues to this day, and is exemplified in its purest form in the current war in Ukraine.

But expanding empires always find pushback. Much of the most effective pushback against Russian expansion came from the British Empire beginning in the 19th century. The British called it the Great Game in the 19th century, while the Americans called it Containment during the Cold War. In reality, these policies are the same. This active pushback continues to this day — and so we have a Western-backed war in Ukraine.

It’s been a long time coming, and started nearly two centuries ago.

The Great Game and Russian Containment

Russia was on a roll in the 19th century. It had a population boom that lasted generations, and had expanded to encompass much land it no longer controls, including huge amounts of territory in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The Russian Empire of the 19th century was a vast, diverse country — a true empire. For reference, around 17% of the Empire’s population in 1897 were Ukrainian. Their central Asian holdings extended south to Afghanistan and Persia (modern Iran).

The British controlled the Indian subcontinent, wielding enormous influence, and so pushed back against Russian expansion while expanding their own power. This was called The Great Game, and the term specifically refers to British attempts to curtail Russian expansion in Central Asia, with a notable flashpoint in Afghanistan — which both empires found to be a nasty quagmire. The British invasion of Afghanistan in 1838 was one of the biggest disasters of that century for the UK.

In case you’re curious, the curious bit of Afghanistan that sticks out to the east to border China was put there to prevent the British Raj in India from having a direct border with the Russian Empire. It exists to this day.

As a side note, the movie The Man Who Would Be King does an excellent job depicting later British involvement in Afghanistan. It’s got Sean Connery. Well worth a watch.

Central Asia wasn’t the only place Britain and Russia clashed. Another notable 19th-century flashpoint against Russian expansion was in Crimea, which hosted the eponymous Crimean War of 1853-56. It featured a coalition of western European powers allying against Russia to prevent Russian expansion there.

You may be noticing a trend here.

In 1871, after trouncing the French, Germany formally became a unified country. The peace architected by Otto von Bismarck in the following decades fell apart after it was taken over by his intellectual inferiors. In addition, the peace collapsed due to outside fears of German power. One of Britain’s prime foreign policy objectives during this period was ensuring that Russia and Germany did not ally, since such an alliance would understandably be terrifying for Western Europe. The British succeeded in this endeavor, but their success led to the disaster of the First World War — which in turn led both Russia and Germany to collapse and slip into totalitarianism.

While the USSR was a staunch ally of, well, the Allies in the Second World War, the tryst between the West and the USSR ended the minute the war was over. And with Britain a spent force, the US was the only democratic power left standing.

The Great Game Goes Global

The French historian Amaury de Riencourt argued that historical trends work like ripples in a pond — they look the same and come from the same source, but get bigger over time. I agree. I prefer to call this phenomenon the Great Fractal, which I’ll write about in a future post, but the idea stands.

Britain passed the torch of containing Russia to the United States in the 20th century, and that’s what’s happening still in the 21st. Whether intentional or not, the United States has progressively adopted aggressive British foreign policy habits and abandoned its traditional, detached, business-first approach to diplomacy. This trend in American foreign policy has accelerated steadily over the past 80 years, and is approaching terminal velocity.

As a side note, one reason that Americans specifically have such trouble understanding Russian concerns is that the countries are polar opposites in terms of geography. The United States is impervious to invasion, with weak, friendly neighbors to the north and south and the world’s largest moats to the east and west. The UK, similarly, is surrounded by a giant moat that has helped define its foreign policy. The US has never been successfully invaded and likely never will be, and the last successful invasion of England was in 1066 AD.

As noted, however, Russia has been invaded again and again, and with devastating consequences. So, it’s not crazy on their part that they might be a bit touchy about border security. Consequently, they’ve pushed their borders as far away from their heartland as possible.

Americans love to believe that they invented the policy of Containment — specifically, that George Kennan did. In reality, it was just the Great Game taken to the global stage. It aimed to stop the spread of communism by pushing back at all points of expansion, which led to, among many other conflicts, the Korean War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan. This was no different than the Great Game — just bigger ripples in the pond.

Cuban Missile Crisis Revisited

For reference, the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 was the closest the world has ever come to full-blown nuclear war. It was solved by back-door diplomacy, in which President Kennedy agreed to withdraw US nuclear missiles from Turkey in exchange for the USSR removing missiles from Cuba.

Robert McNamara, Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense at the time, had a lot to say about how the Cuban Missile Crisis got resolved. This interview is worth reading in its entirety, but here’s a crucial — and ominously familiar — excerpt:

Interviewer: How on Earth did we survive, and who gets the credit?

McNamara: Luck. Luck was a factor. I think, in hindsight, it was the best-managed geopolitical crisis of the post-World War II period, beyond any question. But we were also lucky. And in the end, I think two political leaders, Khrushchev and Kennedy, were wise. Each of them moved in ways that reduced the risk of confrontation. But events were slipping out of their control, and it was just luck that they finally acted before they lost control, and before East and West were involved in nuclear war that would have led to destruction of nations. It was that close.

We’re again as close as we’ve ever been to nuclear war. If the Cuban Missile Crisis is the most dangerous situation the world has ever been through, this Ukraine war rivals it. What’s worse is that our leadership is far less wise than our leaders then, who had all seen the horrors of war in person — and did not wish to revisit it. Rather than de-escalate, our current leaders — especially those in the West — seem hell-bent on bringing this war to a boil. They’re arrogant, ignorant, and foolish, and have no idea what kind of fire they’re playing with. Or, if they do know, then they’re actively evil.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, and Russia was broke, weak, and alone, the US had the chance to befriend and ally its former foe, as it did with great success in Germany and Japan at the end of the Second World War. Clearly, the US chose a different path this time around.

So, why has the US been so aggressive towards Russia despite the collapse of the USSR and Russia’s abandonment of communism? Why view a Russia with a steadily declining population and an economy smaller than Italy’s as a grave threat? Why expand NATO ever closer to Russian borders, despite promises of “not one more inch” of expansion? What gives?

The truth behind that is a bit strange, but it’s there regardless. It all started with one British strategist in 1904.

Mackinder’s Heartland Theory: Acolytes Aplenty

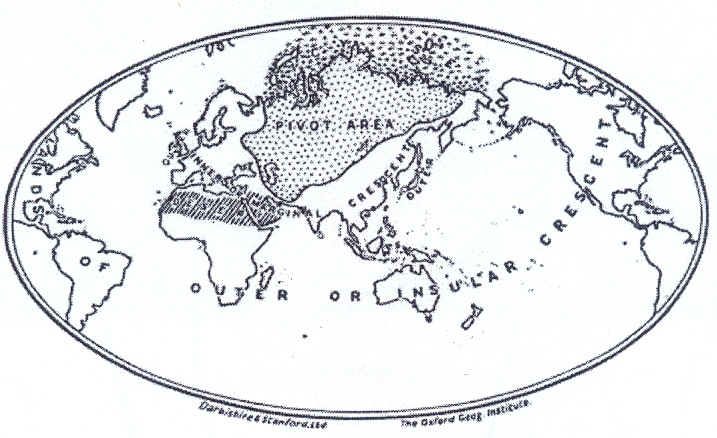

In 1904, a British strategist named Halford Mackinder submitted a paper entitled “The Geographical Pivot of History” to the Royal Geographical Society. In it, he argued that the nation that controlled Eastern Europe and Central Asia would dominate the world in due time. In a way, it was an ex post facto explanation for Britain’s policies in Central Asia.

His reasoning was based around his concept of the World Island, which encompassed Eurasia and Africa. As the world’s largest landmass and with by far most of the world’s population, controlling the World Island was a sure path to world domination.

In this World Island, he identified what he called the Heartland — the area that covers far Eastern Europe, Siberia, and Central Asia. Take a look at the map below. The Pivot Area is the Heartland.

While previously this area had been impervious to invasion due to its size, he argued, railroad had opened up the area to industrialization and, due to both the strategic location at the world’s center and the enormous resources therein, whoever controlled it would end up controlling the world. As he said,

“Who controls Eastern Europe controls the Heartland. Who controls the Heartland controls the World Island. Who controls the World Island controls the world.”

Now, let’s get something straight: I think this theory is a steaming pile of horseshit. Most importantly, the vast majority of what Mackinder dubbed the Heartland is uninhabitable or sparsely populated. It makes sense on a Risk board, but not in the real world.

But it doesn’t matter what I think — Mackinder influenced generations of strategists. One of his most notable acolytes was Zbignew Brzezenski, who was a chief architect of American foreign policy for decades in the mid to late 1900’s.

The Great Game Gets Its Groove Back

Brzezenski published a book in 1997 that clearly relied on Mackinder’s theory for Brzezenski’s prescriptions for American foreign policy in Eurasia. As a brief Foreign Affairs review that year noted,

“The heart of the book is the ambitious strategy it prescribes for extending the Euro-Atlantic community eastward to Ukraine and lending vigorous support to the newly independent republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus, part and parcel of what might be termed a strategy of ‘tough love’ for the Russians…Russia, in effect, is to be accorded the geopolitical equivalent of basketball's full court press.”

Brzezenski points to four pivot points that would be crucial for any rising power in Eurasia. These are:

Iran, which has been in a cold war with the West since 1979

Turkey, which is currently a NATO member, but undergoing hyperinflation and instability, and has a strong possibility of going their own way soon.

Azerbaijan, which is currently fighting Armenia, essentially a Russian vassal state.

Ukraine, where the main event is taking place.

So, there you have it. And in case you’re curious who’s currently carrying the torch for Brzezenski these days, look no further than Victoria Nuland — our current Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs and long-time foreign policy veteran who’s largely worked in the shadows. As a prescient piece in Salon penned on January 19, 2021, wrote,

“Nuland also wants to confront Russia with an aggressive NATO. Since her days as U.S. ambassador to NATO during President George W. Bush's second term, she has been a supporter of NATO's expansion all the way up to Russia's border…Victoria Nuland would be a ticking time-bomb in Biden's State Department.”

This was written before Nuland was given the position, and just look what’s happened. Nuland was largely behind the US’s role in supporting the 2014 Maidan revolution in Ukraine, during which she famously said, “Fuck the EU.” Nuland and her husband Robert Kagan were also a key part of pushing the disastrous Iraq invasion in 2003, just to give you an idea of just how hawkish they are.

The 21st Century Great Game: Now with Nukes!

So, here we are, playing out long-term foreign policy objectives officially set more than a century ago. Our leaders suffer from a severe lack of imagination, and have committed the world to a fight that did not need to be more than a border skirmish. This war didn’t need to happen at all, in fact, and could easily have been avoided. That Kamala Harris said she admired Ukraine’s desire to join NATO merely days before the invasion is a clear indication of how much the US has intentionally upped the ante.

It’s no accident this war is happening in Eastern Europe. Ukraine is a pawn in a centuries-long Great Power chess match, its people caught in the middle. As bravely as they fight, the outcome of this war is unfortunately not up to them. With the two biggest nuclear powers in the world squaring off on their turf, they’re in an impossible situation and have my full sympathy.

For strategists, this conflict is a necessary step in ensuring a great rival doesn’t emerge in the form of a reinvigorated Russia. This situation presents an opportunity to crush Russia once and for all, and to ensure it can never again be a real threat. This kind of thinking is counter to American and Western interests in its entirety, where people are suffering economically far more than expected. It’s not worth it — unless you’ve drunk the Heartland Theory Kool-Aid.

For Russia, losing this war is not an option — with a demographic crisis already in progress and worsening, this may be their last chance to flex their military muscles until their demographics recover. But Russia has faced down some of the worst fights in history and come out the other side. It’s never a good idea to underestimate Russia.

Consider that countries in the flatlands of Eastern Europe can and have disappeared in horrific fashion. Flatlands produce some of the fiercest warrior states the world has ever seen. The plains of what’s now northeast Germany and northern Poland gave rise to Prussia, which has often been referred to as a military with a state instead of a state with a military. Geography very often determines foreign policy, which in turn determines the ethos of a state.

Prussia, the progenitor of modern Germany, no longer exists either as a political entity or as a culture. That’s largely because it came into conflict with Russia in the form of the USSR, who erased it from the map in the Second World War. The city of Kaliningrad was for centuries known as Koenigsburg, home to Emmanuel Kant, and was the capital of East Prussia. It is now almost entirely ethnically Russian. In flatlands, only the strong survive.

This dynamic in Eastern Europe has never changed. A smart United States would have stayed the hell out of European affairs as we did until the First World War, and as the nation’s founders intended. But it’s been captured by ideologues. They have to go. The war has to stop. This Great Game is not a game — it’s quite possibly the prelude to the end of civilization as we know it.

What an article...

awesome work